Restoring 'nature's kidneys' creates cleaner drinking water, saving towns money

A new study shows wetland restorations reduce pollution, lowering treatment costs for utilities.

Wetland restorations can yield significant economic benefits for communities by improving water quality in streams and lakes. This reduces the strain on water treatment plants, saving them money, according to a new study.

Wetlands are often called “nature’s kidneys” because they filter out pollutants. The study in the Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists examined 30 years of data on federally funded wetland restorations in the Mississippi River Basin.

Studying the water quality benefits of wetlands

Nicole Karwowski, an economist at Montana State University, and her collaborator Marin Skidmore with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign combined water quality data with information on wetland restorations in the Wetland Reserve Easement (WRE) Program.

They then compared the water quality in areas with and without the restorations.

The differences were clear.

Both ammonia and nitrogen concentrations were reduced in areas with wetland restorations, with the benefits extending to waters downstream. It generally took two to three years for the reductions to start taking effect.

Fewer pollutants in the water downstream of the wetlands reduces the demands on local water filtration systems that purify drinking water.

Removing nitrogen is mandated by national drinking water standards. High nitrate and nitrite levels can be lethal to babies, causing shortness of breath, or “blue baby syndrome.” Primary sources of nitrogen include excess fertilizer, leaking septic tanks and sewage.

But removing nitrogen is expensive for water treatment plants, and high nitrate levels have been among “the top three violations of safe drinking water standards for over two decades,” according to the study.

Karwowski’s research estimated that local communities saw tangible cost savings from restoring wetlands, with some larger communities saving up to $17,000 per year through reduced water purification costs.

“That can be meaningful, especially for smaller rural towns,” Karwowski said in a statement. “The cool thing is, we’re seeing that federal dollars are going toward this program, and it’s local municipalities that are benefiting.”

While utilities serving large populations or that source water from areas with heavy agricultural activity are estimated to receive the greatest cost savings, smaller utilities would get the highest relative benefit.

The researchers estimate that the restored wetlands collectively generate annual benefits of around $200 million in over 9,000 wetland easements in the Mississippi River Basin, as of 2018. That’s around 1.7 million acres, about the size of Delaware.

The authors conclude that wetland protection projects could pay off within 20 to 30 years if strategically targeted, for example by targeting specific agricultural regions.

What is the Wetland Reserve Easements Program?

The program provides incentives to landowners to voluntarily remove agricultural land from production in perpetuity. Only fields that are either converted wetlands or farmed wetlands are eligible, and farmers are paid a one-time per-acre fee.

The land itself stays in private ownership, but the wetlands are permanently protected through an easement.

NRCS staff then restore the wetlands by planting native species and restoring the hydrology by removing tiling and building berms.

This improves downstream water quality because the new wetlands don’t get new applications of nitrogen fertilizer or other agricultural additives, and they also filter out pollutants.

The WRE program is funded through the Farm Bill and the Inflation Reduction Act, which cover the costs of purchasing the wetland easements and restoring the wetlands. Three million acres were enrolled in the program in 2022, according to the study.

Know anyone who might enjoy this article? Feel free to share it!

Why are wetlands important?

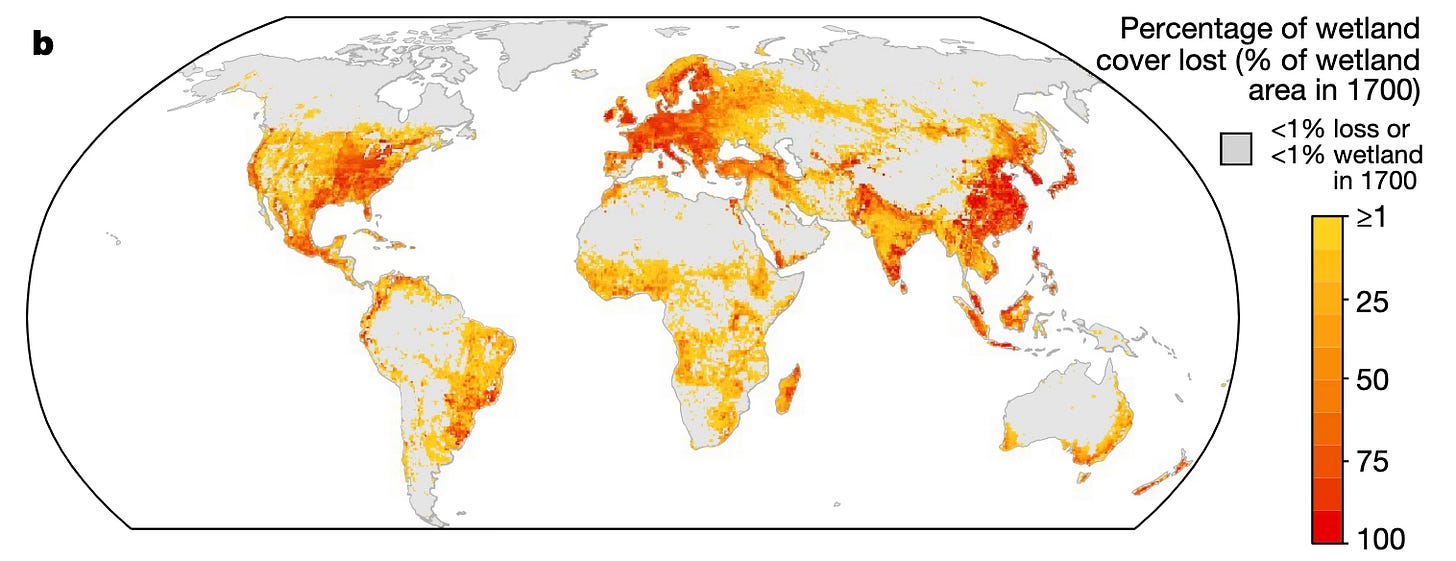

Wetlands are in rough shape everywhere – around one-fifth have been lost globally, and more than half of wetlands are gone in Europe, most of the United States and China. Some European countries – including Ireland, Germany, Italy and the UK – have lost more than three-quarters of wetlands.

They are now disappearing three times faster than forests worldwide, with serious consequences for people and nature.

Humans depend on wetlands for clean drinking water, flood control and shoreline erosion protection. They’re also a source of beauty, offering recreational opportunities from canoeing to photography, hiking, hunting and fishing.

Wetlands are vital for biodiversity as well: 40% of plants and animals live or breed in wetlands, and they provide essential stopover habitat for migrating birds. In North America alone, more than 4 billion birds use them as stopover and wintering habitats every year.

Yet wetland loss in the U.S. has accelerated since 2009, and they are now more vulnerable than in decades after the Supreme Court’s 2023 Sackett v. EPA ruling, which drastically limited the definition of protected waters under the Clean Water Act.

Under the new interpretation of the act, only those wetlands that have a “continuous surface connection” to “streams, oceans, rivers and lakes” are protected. By some estimates, up to nearly two-thirds of U.S. wetlands are now at risk of filling or draining.

“Protecting these unique ecosystems is something that is very valued in Montana given the love of outdoors and the abundant recreational opportunities,” Karwowski said in a statement. “My hope would be that in the future we continue funding programs like this, because we realize that there are valuable effects going toward our communities, especially our rural communities.”

Not ready to subscribe? Consider buying me a coffee (or a beer…). Any support is greatly appreciated!

Waste lands, brain dead splashes, parcel redirected cum, juvenile hopes, drenched curves, wetlands. Black crowned night Heron.